Buy Underground:

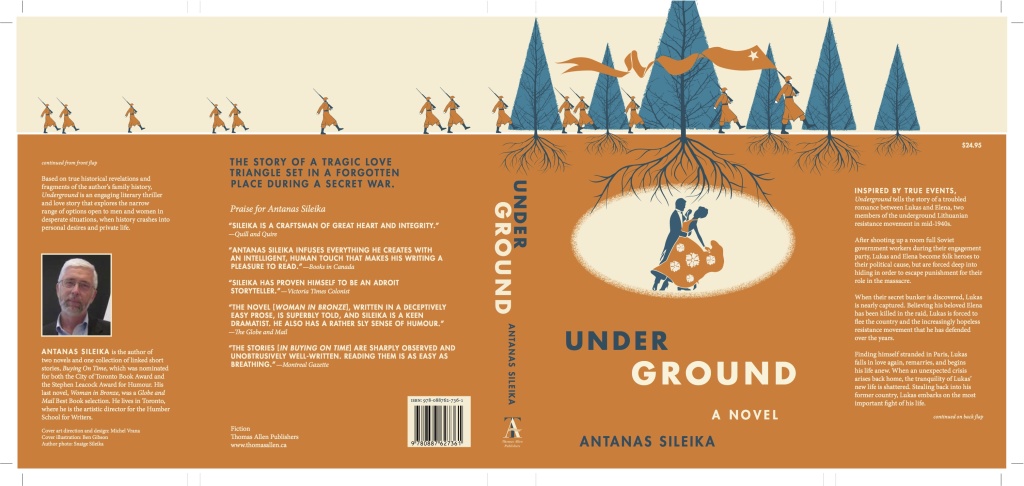

Full wraparound cover below:

REVIEWED BY DONNA BAILEY NURSE

From Saturday’s Globe and Mail

Published Friday, Apr. 08, 2011

How are we going to survive unless we turn our hearts to stone?” a comrade warns the hero of Antanas Sileika’s Underground. The question is an example of the elegant thinking that characterizes this rare and compelling chronicle of Lithuanian partisans and their violent struggle against Soviet occupation. Sileika’s third novel follows the military career of Lukas Petronis, whose bravery and commitment to the cause elevate him to legendary status within the resistance movement. Despite his heroism, Lukas keeps his heart from growing hard by falling in love with Elena, the sister of a partisan.

Underground, by Antanas Sileika, Thomas Allen, 305 pages, $24.95

The story begins in 1944 with the Germans in retreat from Lithuania. With their departure, the dream of an education seems viable again, and Lukas and his younger brother, Vincentas, abandon the family farm on the edge of the Jewish Pine Forest for university in the city. Lukas studies literature while his brother enrolls at the nearby seminary. The buildings are dilapidated and the resources limited, but Lukas exhilarates in learning and the lively company of the students.

Unfortunately, the good times don’t last. The Russians have returned; and for the third time in a half-dozen years, Lithuania finds itself an occupied nation. Cattle cars rumble across the tracks – did they ever really stop? – packed with men, women and children exiled to Siberia. The secret police hound those citizens who remain; torture is commonplace, as is execution. Farmers must hand over to the government impossible portions of their modest crops.

Fed up with feeling powerless, Lukas and Vincentas head into the forest to join the freedom fighters. Whereas Vincentas’s spiritual, otherworldly nature could never adapt to harsh partisan life, Lukas takes to it easily. He turns out to be fearless, an excellent shot. In addition, his composition skills are put to good use. He is given the job of gathering international news and writing articles for the resistance papers.

From its opening lines, the novel strikes a haunting note. Some of this has to do with a ghostly presence: the hundreds of thousands dead, more than half of them Jews; a vast Jewish nation disappeared. The strange winter woodland setting also contributes to the tone. A formal military force, 30,000 strong, is scattered throughout the forests where the Russians fear to tread. Fighters reside in lean-tos or deep bunkers. Larger units emerge to engage the army in significant battles, while smaller groups ambush government officials and target organizations. It is in the woods that Lukas meets Elena, the sister of a comrade. The two eventually marry, but only after they massacre several Russian bureaucrats at their engagement party. They become folk heroes.

Sileika evokes the couple’s relationship with tender realism. His depiction of Elena, one of only a few female characters, also impresses. While she possesses curly brown hair and soulful eyes, it is her inner loveliness and determined nature that attract both Lukas and the reader.

We encounter Elena mostly through conversation, and through Lukas’s eyes. It would be nice to know her a little better, to get inside her head. Though dialogue in the novel is generally strong, spoken word never completely conveys a character’s thoughts and motivations.

Sileika’s portrayal of Vincentas suffers from a similar weakness: We see him mostly from Lukas’s perspective. That’s too bad, as Vincentas, who dreams of becoming a priest, represents a major theme in the novel: He embodies the deep-rooted presence of religion in the culture. Government disapproval means priests live in fear for their lives. Nevertheless, ordinary people cling to their prayer books, refer to their beliefs and continue to embrace the sacraments.

The debate surrounding partisan tactics derives from the Bible. “Harden not your hearts,” reads Hebrews 3:8. In one dark, ironic passage, Vincentas encourages a group of students to love one another: “How can you love the country if you don’t love the people in it?” He recoils from killing the enemy, preferring the path of passive resistance.

After a deadly grenade attack, a grief-stricken Lukas is sent away to the West to heal and to drum up support for the movement. The West is an important character in the story. The partisans expect anti-communist America to save them. In Stockholm, Lukas is infuriated by the unruffled neutrality of the Swedes. Blatant British self-interest equally aggrieves him. In Paris, his political sentiments seem out of fashion. Lukas cannot understand why Western governments worry about placating Stalin when Lithuanian people are being brutalized. Déjà vu all over again.

This story picks up speed as it goes along, hurtling into the future and an unanticipated conclusion. On occasion the prose is a little wooden, but often, too, it is full of poetry and wisdom gorgeously expressed. In addition, Sileika elucidates the socio-political context of occupied Lithuania with astounding ease. He gives us a brilliant, highly accessible military history, one that remains largely repressed – underground – in the East and in the West.

Donna Bailey Nurse is a Toronto editor and writer and a frequent contributor to Globe Books.

Underground

By Antanas Sileika

Thomas Allen, $24.95

Ottawa Citizen – May 1, 2011

Asked to find Lithuania on a map, the average Canadian might not point at Europe, let alone the northeast corner known as the Baltics, where it sits with Estonia and Latvia, tucked between Poland and Russia. Home to 3.6 million people, it is one of Europe’s smaller countries, but back in the 14th century, Lithuania’s borders included present-day Belarus, Ukraine and parts of Poland and Russia. That didn’t last long, however; by the 18th century, Russia had annexed most of its territory.

Modern Lithuania declared its independence in 1918, but then suffered under three waves of occupiers starting in the Second World War: the Soviets in 1940-41, the Germans from 1941-1944, and then the Soviets again from 1944 on until the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. at the end of the Cold War.

Under Soviet occupation, the Baltics were swallowed directly into the bulk of the U.S.S.R. With their international borders erased off the map of Europe, it was too easy for westerners to forget they even existed. But Lithuanians never forgot, and when the Iron Curtain began to rust, they were ready. In March 1990, Lithuania became the first Soviet Republic to declare independence, following the fall of the Berlin Wall in late 1989. The Soviets did not give in easily, first blockading the nascent country economically, and then sending in troops to try to reassert control. In early 1991, 14 civilians were killed, but protesters eventually forced the Soviet soldiers to retreat and Lithuanian independence was won.

Toronto author Antanas Sileika’s new novel, Underground, is set in the early days of the Lithuanian resistance movement against Soviet occupation in the mid-to-late 1940s. At that time, the resistance fighters believed they only had to hold on for a short time until the West invaded the U.S.S.R. or perhaps just dropped an A-bomb on Moscow to curb Stalin’s brutalities. Of course, nothing like that ever happened; rather, western nations focused on their own postwar recovery and were reluctant to help even covertly.

Opening in the summer of 1944, the novel’s protagonist is Lukas Petronis, a farmer’s son who managed to survive first the German occupation and then the Red Army’s forced recruitment of local boys and young men. At the end of the war, Lukas was 23 and ready to get on with life. He hoped to study literature and become a high school teacher, or maybe even a university professor if he was lucky. But most of all, “he wanted to get on with things now, to live in a city, to read books and talk in cafés, to see movies and listen to the radio.”

Soon enough, Lukas learned that this would not be possible under the Soviet regime -fellow students disappeared at random, sent to Siberian work camps for spurious antirevolutionary crimes or for no reason other than being Lithuanian.

Lukas ends up in the resistance almost by accident, and since he is more an academic than a soldier, he is tasked with learning English so he can translate BBC radio reports and turn them into propaganda for the resistance newspaper. As time goes by, however, he also becomes a soldier, initially as a sniper because it turns out he has a sharp eye and steady aim with a rifle, but eventually as a full-fledged resistance fighter -and one of the best.

The first time Lukas kills, he feels a profound change: “the strangeness of having committed an irreversible act. Before that moment he had been a student hiding out in the woods. Now he was something else, but the sensation was so new that he didn’t yet know the creature he’d become.”

He becomes very adept at killing, eventually growing to legendary status. Along the way, he falls in love with Elena, the sister of one of his fellow resistance fighters who has to join the partisans, too, a rare woman among dozens of men who live literally underground in hidden bunkers dug in the forest floor. Lukas and Elena have an unlikely marriage, including a honeymoon spent in a private bunker, the only safe spot available to them.

Over the years, Lukas eventually escapes from Lithuania to try to gain support from foreign powers for his country’s cause. He evolves into an effective speaker and writer, and is courted by foreign security services. Eventually he is called back home on what seems, even to him, to be a suicide mission, but one he cannot refuse.

In the novel’s acknowledgments, Sileika reveals that Lukas Petronis is based on a real-life resistance hero named Juozas Luksa, as well as fragments of his own family history. Sileika undertook extensive research as he wrote this book, travelling to Lithuania and talking to the few surviving members of the underground resistance. That research lends this novel a depth of realism, but this engaging story floats above the dry facts of history.

Underground might be described as a historical love story, but it is also a political military/spy thriller. Sileika writes with a spare style that suits the action sequences, as well as the rare moments of tenderness or humour. Entertaining and sometimes shocking, the book describes a little-known period of European history that has been kept underground far too long.