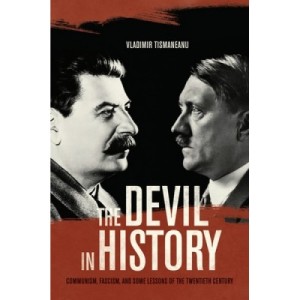

Communism, Facism and Some Lessons of the Twentieth Century

Vladimir Tismaneanu

Hard on the heels of Anne Applebaum and Marci Shore, we find another reassessment of Europe in the twentieth century in Valdimir Tismaneanu’s The Devil in History, a book which is a theoretical study of the century’s two disastrous belief systems. If Applebaum looked at how the structures of civil society were destroyed in postwar Eastern Europe, and Shore looked at the personalities involved in the post-communist landscape, Tismaneanu studies the belief systems of Nazism and Communism that brought Eastern Europe to its present unsettled state.

The evolution of the whole idea of this comparison between nazism and communism is a study in the fast-changing understanding of the last century. For a long time, it was considered reprehensible to compare the two because it diminished the evil of the Nazis. Some thinkers believed every attempt to compare the two was a veiled project to diminish the significance of the Holocaust. The Prague Declaration, a resolution signed in 2008 to study the crimes of communism (Vaclav Havel was among the signatories), in particular has been singled out as just such an attempt to obfuscate history.

Yet when Timothy Snyder visited Toronto to speak about his history, “Bloodlands“, I asked him if it wasn’t unfair to compare these two systems and he responded that if you refuse to compare them, you already have. When I asked Anne Applebaum the same question after her talk in Toronto after the publication of Iron Curtain, she said that this position, the refusal to compare the two, had become marginal. Now, in 2013, the comparison in Tismaneanu’s book is public and most mainstream reviews I have seen of this study only mention the previous “interdiction” on comparison.

When I wrote my 2011 novel about the Lithuanian partisans, I was questioned pointedly by some of my friends about why the Holocaust in Lithuania was not given more space in my book. I thought I had written a story in the shadow of the Holocaust, but clearly some readers were uneasy. I insisted that there were multiple narratives about WW2, and now the subsequent rise in the number of books on the subject of Eastern Europe shows that the multiple narratives continue to appear without, I believe, diminishing the importance of the Holocaust story.

Vladimir Tismaneanu is interesting for his personal history as well as his writing. His parents were committed communists and he was an academic Romanian communist who emigrated to America and began to consider the dictatorships of the twentieth century. His experience is clearly coloured by his past in Romania, where the communist regime devolved into one with strong fascist overtones.

So what does Tismaneanu say these two ideologies, communism and nazism shared? In his eyes, a willingness to purge societies of “former people”, to use the communist formulation. Humanistic values were abandoned in an attempt to build what Tismaneanu calls the City of God, a perverted version of St. Augustine’s idea of heavenly perfection. Thus Jews could be deprived of life and whole classes of people could be executed, imprisoned, or deported under communism.

The critical difference, of course, is that Nazism sought to destroy the lives of a category human beings, whereas communism was not bent on the necessary physical annihilation of the classes it sought to eliminate. Thus there were no ovens in communism.

Tismaneanu is bewildered by western fascination with communism and its apparent return in some places in Eastern Europe. He goes to great lengths to show communism was not merely an idealistic project that went off the rails. It was a murderous project from the very beginning. One of the further differences between communism and fascism is that the former can live on through the party (which is elevated to god-like status) whereas fascism’s appeal frequently lies in the deification of a leader, and once the leader dies, the system collapses.

Facism, Tismaneanu says, is a form of depraved romanticism whereas communism is a form of depraved enlightenment.

Tismaneanu lingers for some time in Eastern Europe, where he says there has been a great disappointment in the post-communist era. People have lost a belief system, and yet they long for one and their reflex is to yield either to embrace ethnic nationalism or revert to communism. What these places need, he says, is societal glue.

Tismaneanu’s book is not for the faint of heart. It is intended for those with knowledge of Hannah Arendt, Arthur Koestler and other thinkers on these matters. Those with less historical or philosophical background will find the going slow, as I did, but well worth the effort for the piercing insights that come out.

The theme I have seen running from Tony Judt to Timothy Snyder, Marci Shore, Anne Applebaum and now Vladimir Tismaneanu is empathy for the individuals who lived between the hammer and the anvil of communism and fascism. When Timothy Snyder was asked why the numbers of deaths he gave in his book were not rounded off, he answered that the death of every individual needed to be taken into account – to round off was to lose sight of the humanity of each person.

The humanity of individuals and the tragedy of the twentieth century in Eastern Europe continues to open up as more and more books are being written.

By coincidence, I was speaking to a group of Balts about my own novel two days ago at the Estonian Hall in Toronto, and I was asked by an audience member if the story of the Baltics was eventually going to come out in the west. I said it was indeed coming out, but perhaps not in the way the questioner expected or hoped. The subject of the history of the twentieth century, particularly in Eastern Europe, continues to be a minefield, but the unexploded bombs of the past are being dug up more and more often now. One thing is sure. On the way to broader understanding, there will be more explosions of controversy.