A Talk Given for the Goethe Institut at the Thomas Mann Festival in Nida, Lithuania,

July 13, 2019

Let me begin my consideration of European homelands of the imagination from afar both in geography and in time.

I wish to take you to the edge of Weston, a small town in Canada in the nineteen fifties and sixties. This town is expanding into the farm fields around it, fields which have been bought but not yet developed – within these unplanted fields stand a few abandoned farm houses with broken windows, and on the ground lie ponds slick with slime; the untended vegetation is beginning to include Queen Anne’s lace, milkweed, and poplar seedlings.

If Weston is about to consume the countryside with new suburbs, then the town itself, a main street with shops, is being eaten by the expanding city of Toronto, which will finally take it in one bite in 1967, when the place will lose its own mayor and police force. But Weston will sit inside Toronto for a very long time, like the undigested body of a frog inside a snake.

This is where I was born in 1953.

In this suburb-to-be, not yet a suburb, lived a scattering of working-class and middle-class families, all products of the war and then the postwar boom. In North America we remember this time fondly as one of wealth and growth and slow enlightenment about civil rights, but it had had its horrors. My friend of Japanese heritage, Mike Adachi, had parents who were interned as aliens during the war, and lost all of their property. My friend Allen Jamieson’s father had been a Canadian soldier in Hong Kong when it fell to the invading Japanese army, and he spent the war in a prisoner of war camp where he lost most of his sight due to malnutrition.

And then there was my family, Lithuanian immigrants who had fled the Red Army with their baby in 1944, and lived in a Displaced Persons’ camp in Oldenburg where they had another baby, before emigrating to Canada in 1948 and eventually giving birth to me.

If I sat in the kitchen with my mother and father as they were drinking tea after dinner, and if they were not rushed, they might tell me the story of their last home in the Lithuanian city of Alytus, which they had fled in the summer of 1944. I possess one of the few family photos of that time, taken about a week before the arrival of the Red Army. My mother smiles innocently in the garden and holds the hand of my toddler brother, not quite a year old. On the other hand, my troubled father looks down, a briefcase in his hand, his mind clearly elsewhere.

My naïve mother had said to the maid they would need to clean the upstairs windows soon, but the maid replied the Soviets would be there within a week, so there was no point. When my mother asked my father about this, he explained he had a horse and wagon ready, a store of food, maps and currency and they would leave within a few days, as soon as they could hear the sound of the Soviet artillery. After all, his brother had spent a year in prison under the first Soviet occupation, and was lucky enough to escape alive, but lost all his teeth during beatings under interrogation by the communists.

Ever more successful in Canada with the passage of time, my mother and father bought a new car in 1958, as well as a lot near a beach where they intended to build a summer cottage. But for all his success, my father had a farmer’s distrust of extravagance and refused to buy a radio for the car. Instead, he and my mother talked, as we three boys in the back seat leaned forward to hear the story of fleeing Lithuania. My mother learned to recognize the sound of airplane engines because the Soviet planes strafed the columns of refugees. If she did hear a Soviet plane, she ran for the ditch with her sister, and my father took the baby to join them. Their little horse was forever calm, and stood waiting on the road as the bullets flew all around. My mother and father remembered that horse fondly. A kind German officer told them one night to hurry across a bridge before it was blown to slow the advancing enemy, and the exhausted horse managed the job, bringing them eventually all the way to Oldenburg and safety. There they hunkered for a few years in a DP camp, gave birth to another of my brothers, and eventually came to Canada where I was born.

We grew up in perhaps the best place and time for people like us, when the economy was expanding and no wars were being fought on our land. We were like survivors of a shipwreck, people who landed on a paradisiacal shore, the Swiss Family Robinson with a refrigerator and a car. We were foreigners, but unremarkable among many other European immigrants. Millions died and millions fled; millions were displaced like pieces recut to form a new jigsaw puzzle.

But for all of its wonders, for all of its wealth, Weston was not my homeland, even though it is where I grew up, a place which I remember so fondly to this day – outside the smell of cut grass lawns and the sound of young men washing their cars for Saturday night dates; inside the sound of the vacuum cleaner bumping against the baseboards by the carpet and the smell of bacon and eggs being fried for lazy weekend boys.

The immigrants of that time were called Displaced Persons, or DP’s for short, and I somehow remained profoundly displaced in the land of my birth.

Consider the work of Salman Rushdie, who has written about imaginary homelands too, although his book of essays has to do mostly with post-colonialism and Britain. I take an important observation from Salman Rushdie. In his view, the migrant is the central or defining figure of the twentieth century. Tantilizingly, Rushdie also writes that we live in ideas and through images we seek to comprehend the world. That is precisely what I am doing here.

I focus on European homelands. Partially this is a reflex, an unthinking action. But beyond that, as a man of European heritage, I feel I have some right to this enquiry in a ways I would not have elsewhere.

So we should agree with Rushdie that there is nothing remarkable about emigrants of that period. Many if not most of their children managed to assimilate in the places where they landed, often retaining some fondness for their heritage such as a taste for the food of their parents and grandparents. Provided they were safe, some might even have gone back to the places their parents came from, such as Ireland or the United Kingdom.

But the fact of the iron curtain made going back to Lithuania impossible. It was not merely a question of the iron curtain. Other countries lay behind it too, but the Baltic States, Lithuania among them, had been incorporated into the Soviet Union and thus disappeared from the map.

Imagine, a whole country disappearing! Parts of other countries disappeared, such as the land we stand on in Nida now, but Lithuania’s vanishing was total. At first, people in the west might have remembered its name, but as time passed, they forgot all about it.

Let me return for a moment to Weston, Ontario, the place where I was born. We children felt displaced there, not only because we came from Lithuania, but because in the dawn of the television era, Weston was so remote from the centres of the world as to have no meaning in and of itself. For children of the era, television and comic books were our true homes, and the places depicted there were American. Our true homelands lay in the exciting places of adventure like the western ranch on Bonanza, or the funny and urbane New York of The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Honeymooners, and I Love Lucy, or the Hollywood of The Steve Allen Show. In comics it was Gotham City for Batman or Metropolis for Superman, or again, New York City for The Fantastic Four.

I lived with so many levels of exile, I barely existed, indeed felt as if I did not exist at all. A young man with parents from nowhere, a place that literally did not exist on the map, lived in a place that was almost nowhere. I was not alone of course, because the Estonians, Latvians, and Ukrainians felt the same way. We even had our own basketball league, which might as well have been called “The Vanished Nations League.”

Everyone needs to be someone, and every someone needs to be someplace. I could solve the problem of my nonexistence by becoming a writer. Proof of my existence would then lie on the page. But I could not easily solve the problem of being some place. I have been searching for homeland for most of my life, and frequently it has been a homeland of the imagination.

My first homeland of the imagination lay in the ruins of the British Empire, called in my time The Commonwealth. Every Canadian elementary school room had a map in it, and on every map the countries that belonged to The Commonwealth were coloured pink. Weston was farther from London than it was from New York, but it was closer to my childish heart because I felt that everything within the vast pink expanse belonged to me. My homeland was England, but I might find echoes of this homeland in India, Australia, or South Africa if I so chose. As I began to turn into a compulsive reader, I read the story of this imaginary homeland again and again, through Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, Elizabeth Nesbitt, and H. G. Wells. Their home was my home, and their language was my language, even though the writer I most admired, the poet Dylan Thomas, was actually Welsh.

If a homeland is a place that brings you comfort and security, this imaginary European homeland of England and by extension The Commonwealth, consoled me for many things – for being a failure at sports, for living in the godforsaken emptiness of Weston, and for having a father who never really adapted to Canada, and a mother who was often very sad. My one homeland of the imagination, the English one, was full of bravado and empire. My other one, my Lithuanian potential one, was full of melancholy. These homelands were like two angels on my shoulders, or to be Freudian, my English homeland was my childish superego, and my Lithuanian homeland was my id.

But the English homeland did not last. It was destroyed by the offhand comment of my friend Vaughan’s grandmother. He was an English boy and when his grandmother came to Canada to visit him, I stood in the corner of the room, filled with admiration for her very English Englishness. When I was introduced to her, she said: “What a pretty boy. Such a shame he’s a foreigner.”

Such a fragile homeland this Commonwealth was! So easy to destroy with an offhand comment! And I should not wring my hands about this comment because it awoke me to the reality of my condition. The Commonwealth was not my homeland, imagined or otherwise. I would need to go looking for my homeland, but from the ruined British homeland I took one prize – namely the English language. It was the tool I would use to forge myself and to find my own homelands as well.

Well then, what about the homeland my parents had left behind? My mother had bouts of gloom for the loss of it. She spoke repeatedly about the place where her own mother lived until she died in the late fifties. This very same grandmother once wrote to say how sad she was that she could never meet me because she wished to buy me a bag of candies. To a child, a bag of candies represented a fortune as well as love, great wealth when candies were sold by the pound, but no one ever bought them for me because my grandmother lived in a land that did not exist.

This homeland of my parents therefore existed for them, but it did not exist outside the walls of our house or the walls of our Lithuanian church, or the yard of our Saturday morning Lithuanian school. If my Commonwealth English homeland came to me through its authors, my parents’ Lithuanian homeland came to me through the oral recounting of my their childhoods. These stories recounted a life in the equivalent of the city of Troy before it was destroyed, and their great migration was the Aeneid. Once Troy has been sacked, there is no going back.

One of my lost European homelands, the Commonwealth one, was written, and the other homeland, the Lithuanian one, was spoken, but both were imaginary.

I should add that my mother did read me a few stories from Lithuanian books. Two of the stories were by Jonas Biliūnas. The first was called Brisiaus galas, about an old dog who dreams of adventures with his master, only to be shot by this master when the dog is too old. The other story, Kliūdžiau, was about a boy who takes his bow and arrow and in a moment of bravado shoots and kills a neighbourhood cat, after which he is filled with remorse. The third memorable story was Grybų karas, in which the mushrooms decide to go to war, but die of rot before they can execute their plan.

My Canadian friends laugh merrily when I tell them of these Lithuanian children’s stories, so dark and so pessimistic compared to the happy tales of Disney.

So what about my parents’ homeland? It could not be mine. Their homelands were both their childhood homes and family, and their youths as well, when they were young and easy and green and carefree. In my own cocky youth, I considered my parents to be nostalgic, and there was no more dismissive term in my adolescent vocabulary. Their memories were not my memories and I was casually cruel about their irrelevance. I would find a homeland, perhaps, but I would find it myself.

If I did not feel Canada was my homeland, and if the Commonwealth would not have me, and the dismal Lithuania was not for me either, what was I to do?

My search for homeland went into the university library where I spent many days and nights when I was a student and the place where I wandered the stacks of the European history section, searching for the word “Lithuania” in the indexes of European history books. Often I did not find the word and even when I did, the entries were always brief and sometimes dismissive, as in a leftist history which referred to interwar Lithuania as worthy of a “comic opera.” Disturbed and wounded, I would return to a carrel where I was studying English literature and might be writing a paper on Ernest Hemingway or William Faulkner.

So the language of my abandoned Commonwealth homeland took me to other ones, the Northern Michigan landscape of Hemingway’s The Nick Adams Stories, or the YoknapatawphaCounty of Faulkner. Theses were homelands I occupied for a while, though not European ones, unless perhaps the Italy of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, a novel whose hopelessness appealed to my youthful nihilism.

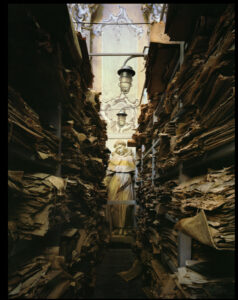

That library was a kind of refuge – bookish men, women and children have found asylum in libraries ever since wars, competitive sports, fractious parents, whining children, moronic television shows, leaf blowers, motorcycles, food processors and other dangers or irritants have driven them away from the rest of life. Libraries have been celebrated often, most notably by Alberto Manguel, who spoke of sitting in his French provincial private library, listening to how the books connected to one another at night.

But the library is not the destination of this voyage of European homelands of the imagination. It is instead a point of transit, a portal. It is the place that takes you to the homelands, whether in fiction or nonfiction because both are imaginary once they are in books and no longer concrete.

Through it, I might have entered one of Ray Bradbury’s homelands, which sounds so warm and so strange in The Martian Chronicles:

It was quiet in the deep morning of Mars, as quiet as a cool black well, with stars shining in the canal waters, and, breathing in every room, the children curled with their spiders in closed hands, the lovers arm in arm, the moons gone, the torches cold, the stone amphitheaters deserted.

Through that same portal, with so many choices, I might have entered into one of Norman Davies’s histories – because Lithuania was not the only place that had disappeared over time. This very fine historian, the author of many volumes but for us most pointedly of Vanished Kingdoms, says of the ancient Prussians of the tenth century, that they lived on the Amber Coast and their name might mean something like “Water Tribes” of “People of the Lagoons.” Such potential romance in this sort of naming! Such potential for a homeland, but perhaps a little too far back in history.

What need for all this going into fantasy or ancient history through libraries when Lithuania gained its independence decades ago, and thus I could have found it to be my homeland? My son lives there and so does my grandson, but the land of Lithuania is more often the land of the supermarket called Maxima for me now when I am on the street, or other stores where I go to buy snacks for an overactive five year-old. But my imagination does not inhabit this world. It does not provide me comfort or space for roving in the way my imagination seeks.

Umberto Ecco says we know perfectly well the real world exists, but we decide to take the fictional one seriously – let me modify that to say we take the imaginary world seriously.

I have taken you on a rambling journey and it wouldn’t be fair to leave you without reaching my goal. Through this library portal I have indeed found my European homeland, and it remains an imaginary one, an evocative one as strange as the Mars of Ray Bradbury, but so close I feel I inhabit it in my mind if not in my body.

I am speaking of another writer I found long ago, namely Czeslaw Milosz, who in his Issa Valley and Native Realm wrote with great love and detail of his childhood home in a crumbling Lithuanian manor house where everyone spoke Polish, the language of his writing too. This landscape of creaking wagons and birdsong among the trees is alive to me. I can smell it and feel it and find comfort in it.

But it is only one part of my European homeland of the imagination. I don’t inhabit the world solely of Milosz because others have evoked this world as well. I think of Tadas Ivanauskas, the great naturalist of Lithuania, the founder of the Kaunas zoo. In his Aš Apsisprendžiu, he writes of a childhood in a manor house where the hunting dogs sprawled wherever they liked, the lamp oil was measured out each evening, and a barrel of vinegar stood in the living room forever because no one knew how it got there, but since it had stood there since the beginning of time, it might as well continue.

There are others who have written well to evoke their landscapes, not just the inhabitants of manor houses – the former officer of independent Lithuania, Konstantinas Žukas, in his Žvilgsnis į praeitį or the head of Lithuanian counterintelligence, Jonas Budrys in his Kontražvalgyba Lietuvoje, and many other less celebrated, but equally engaging writers who have created the atmosphere of their Lithuanian homelands.

Their homelands have become mine.

These homelands, like those of my parents, are gone from everywhere but the imagination. Czeslaw Milosz himself said upon revisiting his childhood home, that not one stone stood upon another in any recognizable way after the passage of a few disastrous decades. Yet Milosz in most of his later prose works returned again and again to this place because it was the place that had formed him. I who sneered at the nostalgia of my parents learned to respect their views through Milosz.

But critically, both my parents and Milosz spoke of memories, whereas I speak of imaginary European places, imaginary in the sense that I never inhabited them in my childhood and they no longer exist now.

These homelands of the imagination are richly described and welcoming, waiting for me and others like me as if they were chairs by the fire on a cold and windy evening. I enter these homelands in my writing and I live in them in my mind. My novels are nothing more than extensions of these memoirs, but my work is written in English. I step into these worlds and I rearrange the furniture to suit my story, and I add or remove characters as I might invite or not invite guests to a party.

The European homeland of the imagination has certain advantages over a physical homeland. One need not spill blood for it. The imaginary homeland is a danger to no one else. It is a private refuge unless I use it to ask readers to join me. As the American historian Kate Brown says in her Biography of No Place, she writes of a place that no longer exists and the people who no longer inhabit it. I once felt as if I did not exist, and to find my imaginary homeland, I similarly had to go to a place that did not exist anywhere but in books.

I have written here about one of my own European homelands of the imagination, but there are other potential ones. When I am in the Lithuanian village of Lynezeris near the border and my mobile phone registers Belarus, I think of the homeland evoked by Alexandra Alexievich. Here in Nida when I am out on the Baltic beach, my phone picks up Kaliningrad and I think of a long-gone colleague of mine in Canada, Margitta Dinzl, who was carried out of East Prussia on the arms of her mother at the end of the second word war. She spoke so vividly to me of this place, one she had never seen in adulthood, over forty years ago, that I can practically smell it, yet it exists nowhere else but in her mind and now seeded in mine. And when I say seeded I mean exactly that. My imagination begins to work on these places, to make them potential zones of comfort for me and the places begin to grow if I let them.

In her old age, my mother-in-law began to suffer from dementia. She saw ghosts: her dead friend from down the road knocked on her door. What surprised me was another change that came upon her.

She could no longer feel at home. When I rose from her kitchen table in a house she had inhabited for fifty years, she would say to me, “Are you going my way? Do you think you could take me home?” She had begun to disassociate herself from her surroundings. She no longer felt their comfort, their reassuring warmth.

She too had an imaginary home, one that was elsewhere, but she could no longer enter into it. She was looking for it because the search for a homeland is a lifelong quest. Home evolves and shifts.

European Homelands, even imaginary ones, can slip away. We leave them by choice or memory loss, or the world of politics and economics erupts and forces us to leave them. But they are not in one fixed place. We want them because their comfort is as welcome as birdsong in spring, yet this wellbeing can vanish as quickly as a season’s end, and we need to migrate with our imagination to find our homelands again. I am a writer who lives in his imagination and one who has found his true European homeland there, at least for now.

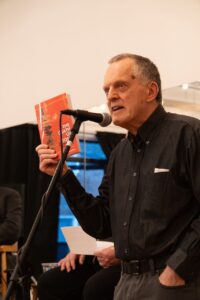

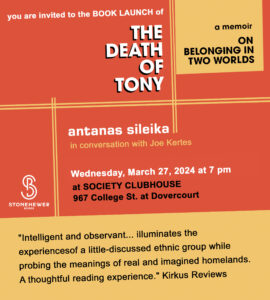

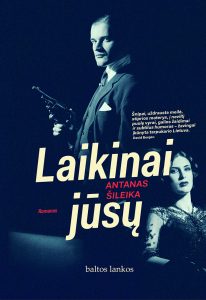

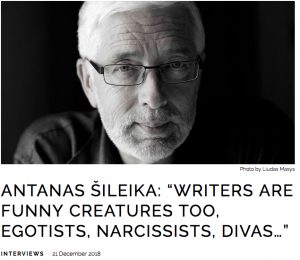

Antanas Šileika

Writers and Some of their Works that Have Been Cited in this Essay in the Order in Which They Appear

Johann Wyss – The Swiss Family Robinson

Salman Rushdie – Imaginary Homelands

Rudyard Kipling

Arthur Conan Doyle

Elizabeth Nesbitt

H G Wells

Dylan Thomas

Jonas Biliūnas – Brisiaus galas, Kliūdžiau

Justinas Marcinkevičius – Grybų karas

Ernest Hemingway – The Nick Adams Stories, A Farewell to Arms

William Faulkner

Alberto Manguel – The Library at Night

Ray Bradbury – The Martian Chronicles

Norman Davies – Vanished Kingdoms

Umberto Eco – The Book of Legendary Lands

Czeslaw Milosz – Native Realm, Issa Valley

Tadas Ivanauskas – Aš Apsisprendžiu

Konstantinas Žukas – Žvilksnis į praeitį

Jonas Budrys – Kontražvalgyba Lietuvoje

Kate Brown – A Biography of No Place

Alexandra Alexievich

Biographical Note:

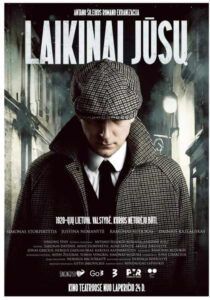

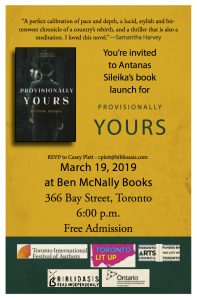

Antanas Sileika is the author of six books of fiction and nonfiction. His most recent novel published in Lithuania and Canada is Provisionally Yours, and its subject, among other things, has to do with the annexation of the Klaipeda region by Lithuania in 1923.

ž

ž