Postscript

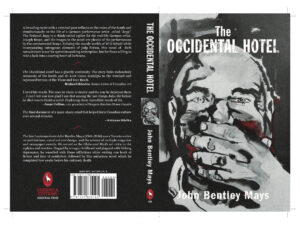

My friend, the writer and critic, John Bentley Mays died four years ago, but he left behind a novel completed just before his death, and it was published recently by Guernica Editions. Here below the image of the book cover is my introduction to that novel, describing what it was like for work through that manuscript with John, the book also has outstanding essays by Anne Collins and Richard Rhodes.

And here is a four-minute video we made about John and the book and a link to a passage published in Open Book.

John Bentley Mays wore shapeless sweat pants and a baggy sweater when he walked into Little Italy’s Bar Diplomatico to meet me. He was unshaven and since he wasn’t wearing a hat, the prominent scar on his forehead where skin cancers had been cut out repeatedly made him look like a war vet of some kind. He was there yet again to discuss with me the progress of the novel he had been struggling with for years.

This version of John was a far cry from the dapper Truman Capote knock-off I’d met along with his writer wife, Margaret Cannon, in the early eighties, when John was a sizzling Globe and Mail critic who made Canadian art essential and important enough to fight about. He could be scornful of sacred cows and worked hard to elevate young artists. A brilliant conversationalist when in good form, he could take a conceit and spin it into a talk worthy of an essay. His writing was a delight to read, full of unexpected turns and insights.

First evangelical, then Anglican, then Catholic, first an alcoholic and then a teetotaller, first art and then culture and architecture critic, he had had his share of ups and downs.

A lifelong depressive, he’d been fed a variety of drugs and gone through a variety of treatments including electroshock therapy, and all of these seemed to work for a while and then failed him. Among the things he carried was a fraught Louisiana childhood—a murdered father and a mother who died young so John was shipped off to older sisters when he was a child.

He left behind his southern gothic background to come north where art and Toronto and his wife, Margaret, were his antidotes to an unhappy childhood worthy of William Faulkner.

The one quality he had was an ability to write though the pain, and now he was writing a novel. We met repeatedly at the Dip to discuss the first fifty pages, then the first hundred pages, and then the first one hundred and fifty pages all the way from 2013 through to 2016.

John always rewrote from the beginning and continued to the current end, so I must have read parts of this novel six or seven times.

I was shocked and appalled, admiring and afraid for his reputation as John wrote an unconventional piece of work with one of the most horrible anti-hero narrators I had read since John Fowles’ The Collector. And there was no escape from this monster, who suffered no comeuppance, but who, like a poisonous spider, sat in a web with different threads: elements of art criticism; ironic comments on modernity; outlandish pulp adventures worthy of Edgar Rice Burroughs; mood pieces like those of W G Sebald; and explorations of Nazi youth ideology as it affected the late German artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986).

John was fascinated by Joseph Beuys, and one of the unconventional aspects of this novel was that it contained images from some of this artist’s performance pieces. The stand-in for Beuys in the novel was a character named Jupp, someone John used to explore in a fictional way Beuys’ own Nazi youth.

Beuys had been a Luftwaffe pilot during the Second World War, and later biographies accused him of having been not only a soldier, but a true Nazi. John both admired Beuys and was deeply troubled by this past. John held his dismay and esteem for Beuys in some kind of tension in his mind.

The fictional Jupp was an object of obsession for the narrator of this novel, a murderous, racist southerner holed up in the crumbling Occidental Hotel, a place that is a shell of the American postwar optimism during which it was built. Modernity was a lifelong obsession for John, primarily through its expression in architecture. Some form of modernity was going to free John from his biography of gothic southern history, but it never managed to do so. John wrestled with these two elements for his entire life, dealing with these themes and many others in some of his nonfiction books such as Power in the Blood and Arrivals.

I cautioned John that many Canadian readers would hate this book because it provided no exit. We see various depictions of hell with little solace or redemption. I warned him that he would be confused with the narrator of this book, and he told me the narrator was the man he would have become had he stayed in the south. John said he had no intention of shocking Canadians. He wanted to reprimand Americans, especially after the horror of the 2015 Charleston Church massacre, in which a white supremacist shot and killed nine black parishioners in a church and wounded three others.

For three years we talked about this novel. I suggested that John was dealing in arcana because hardly anyone outside the art world knows who Joseph Beuys was. I accused him of delivering a bleak vision, and he agreed that he was working in the realm of dark romanticism, but would not give up. I was fascinated by this work, which felt decidedly European to me, like nothing else I was seeing in Canada.

On September 2, 2016, John sent me the final draft of his novel. It was highly polished, as all of John’s work tended to be, but I don’t think it was perfect. I suggested he make a few changes to speed up the action in the first part of the novel, and he seemed to agree with my ideas. We made arrangements to meet again at the Dip on September 21 to discuss my notes. On September 16, he died of a massive heart attack after walking up a hill in High Park with his long-time friend, the literary critic, Phil Marchand.

A manuscript by a deceased writer is a hard sell, but Guernica Editions agreed with me that this novel is an important addition to Canadian letters for at least two reasons. First, it is an unblinking look into a heart of darkness of a kind we almost never see in this country. It is frightening and necessary. And second, it is the final document of a razor-sharp mind that helped form Canadian culture over several decades.